If you have any anxiety at all about the future, Warren Ellis will find it, extract it, magnify it, and…make you feel empowered enough to take it on yourself. Ellis, whose career spans decades of filthy-yet-forward-looking articles, books, and graphic novels, is back at it this week with the release of his new novel Normal, a story about rebalancing your head after spending too much time worrying and preparing for the future.

We’re looking forward to reading it, as Ellis has written some of our staff’s favorite stories ever. Here are just a few that have stuck inside our mind-traps over the years…

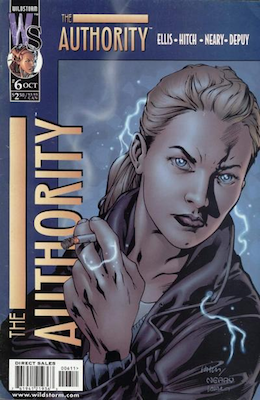

Stormwatch/The Authority

I have a lot of affection for Ellis’s version of the self-directed, fairly dubious superhero team that protects the world as they see fit. But what makes these particular stories, for me, is Jenny Sparks, the superhero I didn’t know I needed. Born at the start of the 20th century, she’s its spirit—a foul-mouthed, chain-smoking, reluctant leader with control over electricity. She was introduced at the start of Ellis’s run on Stormwatch, then became the leader of the Authority, until the century ended—and so did she. But before that, she did everything, influencing the world for the span of her extended lifetime. Jenny wasn’t nice, and she wasn’t fancy; she wore t-shirts and put her hair in a ponytail and had a temper. She embodied so much of what obsessed Western culture in the late 20th century—the electric, the new, the perpetually youthful—but she did all that and got the work done while being cranky and difficult and probably making some really terrible choices. The Authority has its Superman and Batman analogues, but Jenny? She’s her own girl. —Molly

I have a lot of affection for Ellis’s version of the self-directed, fairly dubious superhero team that protects the world as they see fit. But what makes these particular stories, for me, is Jenny Sparks, the superhero I didn’t know I needed. Born at the start of the 20th century, she’s its spirit—a foul-mouthed, chain-smoking, reluctant leader with control over electricity. She was introduced at the start of Ellis’s run on Stormwatch, then became the leader of the Authority, until the century ended—and so did she. But before that, she did everything, influencing the world for the span of her extended lifetime. Jenny wasn’t nice, and she wasn’t fancy; she wore t-shirts and put her hair in a ponytail and had a temper. She embodied so much of what obsessed Western culture in the late 20th century—the electric, the new, the perpetually youthful—but she did all that and got the work done while being cranky and difficult and probably making some really terrible choices. The Authority has its Superman and Batman analogues, but Jenny? She’s her own girl. —Molly

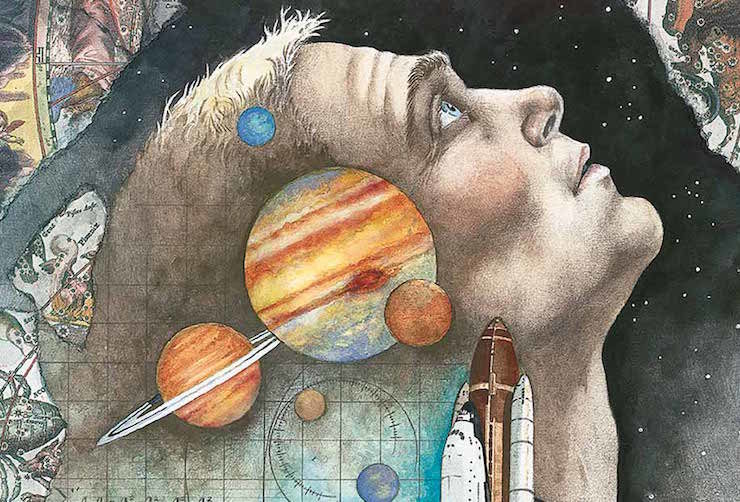

Orbiter

It’s weird to see a happy ending in an original Warren Ellis story. I’m so accustomed to his style being one of determination, grit, and perseverance; where a happy ending isn’t so much about implementing a big fix or stopping a bad guy and more about slowing the avalanche of awfulness just long enough to take a cigarette break.

It’s weird to see a happy ending in an original Warren Ellis story. I’m so accustomed to his style being one of determination, grit, and perseverance; where a happy ending isn’t so much about implementing a big fix or stopping a bad guy and more about slowing the avalanche of awfulness just long enough to take a cigarette break.

Orbiter‘s happy ending is striking within that context, especially since it begins in a bleak future instantly recognizable to Ellis’ readers. The book’s message of hope is even more notable because it is never disingenuous or ignorant of the world it exists within. The entire self-contained story, illustrated by Colleen Doran, is a love letter to the concept of exploration, both of space and of the self. It is fiercely unapologetic about looking to the skies, and about harmony with science, and I love that Ellis takes this stand. Don’t ever stop looking up. Don’t ever stop fighting for the right to explore. Hope comes to the hard-fought. We can rise again.—Chris

Gun Machine

Ellis’s second novel (after the delightfully obscene, often overlooked Crooked Little Vein) sits somewhere between the near-future-is-now of William Gibson’s Blue Ant trilogy and the surreal, intense, sense-of-place-heavy detective story in Lauren Beukes’s Broken Monsters. It’s a murder mystery, sort of, but the murders span decades, and the mystery relies on Ellis’s careful weaving of two threads, one from the past, one from the present. Like Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, Gun Machine is, unexpectedly, a very American story—one written by an outsider who sees our country in a different way. And Ellis’s vision of Manhattan is of a place overrun with both history and technology. It feels more than familiar. It feels right. —Molly

Ellis’s second novel (after the delightfully obscene, often overlooked Crooked Little Vein) sits somewhere between the near-future-is-now of William Gibson’s Blue Ant trilogy and the surreal, intense, sense-of-place-heavy detective story in Lauren Beukes’s Broken Monsters. It’s a murder mystery, sort of, but the murders span decades, and the mystery relies on Ellis’s careful weaving of two threads, one from the past, one from the present. Like Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, Gun Machine is, unexpectedly, a very American story—one written by an outsider who sees our country in a different way. And Ellis’s vision of Manhattan is of a place overrun with both history and technology. It feels more than familiar. It feels right. —Molly

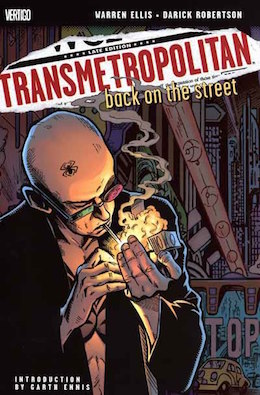

Transmetropolitan

Transmetropolitan was one of those extraordinary ‘90s comics that redefined what comics could be about, how they could look, and how often their characters could say fuck. (This might sound silly, but for a comic that was, at its heart, about the power of freedom of speech, the celebration of cursing is important.) The plot is simple: in the not-too-distant future, Dystopian Hunter S. Thompson renowned journalist Spider Jerusalem gets called out of retirement to write the last two books he owes his publisher. He moves back into The City to cover stories of thawed-out cryogenics pioneers, police violence, celebrity scandals, transhumanist rights protests, and religious riots, but increasingly focuses on exposing the evils of The Smiler, the newly-elected president who may actually be psychotic.

Transmetropolitan was one of those extraordinary ‘90s comics that redefined what comics could be about, how they could look, and how often their characters could say fuck. (This might sound silly, but for a comic that was, at its heart, about the power of freedom of speech, the celebration of cursing is important.) The plot is simple: in the not-too-distant future, Dystopian Hunter S. Thompson renowned journalist Spider Jerusalem gets called out of retirement to write the last two books he owes his publisher. He moves back into The City to cover stories of thawed-out cryogenics pioneers, police violence, celebrity scandals, transhumanist rights protests, and religious riots, but increasingly focuses on exposing the evils of The Smiler, the newly-elected president who may actually be psychotic.

Ellis celebrates the idea that a free, wide-ranging, beholden-to-no-one, no-fucks-given press is the bedrock of democratic society, and in the world of Transmet, as terrible as it is in many ways, good journalism can save lives, and even change the world. But maybe even better is Ellis’ explosion of the Jerk with a Heart of Gold trope. Spider Jerusalem is a terrible man. He has done terrible things to people, treated them like garbage while hypocritically calling out society as a whole for treating the underclass like garbage. He lives in the glassiest house, but makes his living throwing stones. But he also loves his City, loves humanity in the abstract, fights for the underdog, cares about his cat, and wants democracy to prevail. All of these things are true. There is no point where the real, marshmallow-sweet Spider is revealed. There is no come-to-Jesus moment where he realizes he should be nice to his assistants. He’s terrible in the opening panel, and still terrible in the final one, but along the way he saves lives and fights against a corrupt president. It’s all true.—Leah

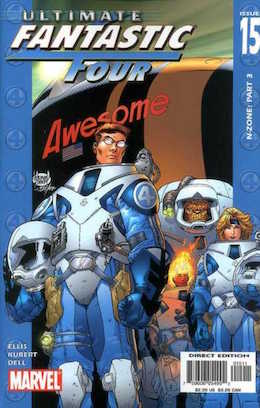

Ultimate Fantastic Four

In the early 2000s, Marvel Comics seized the paranoid sci-fi zeitgeist of the new millennium and reimagined its key characters in that vein via the new “Ultimate” line. What resulted was terrifically vibrant: a Spider-Man who grew up with the internet and who stood at the forefront of genetic science, a cynical Avengers trying to discover their own heroism as they grew out of the military-industrial complex, and X-Men who more than ever represented a marginalized minority population. Ellis provided the final piece: A Fantastic Four as young scientists keen on exploration, activism, and huge society-altering ideas.

In the early 2000s, Marvel Comics seized the paranoid sci-fi zeitgeist of the new millennium and reimagined its key characters in that vein via the new “Ultimate” line. What resulted was terrifically vibrant: a Spider-Man who grew up with the internet and who stood at the forefront of genetic science, a cynical Avengers trying to discover their own heroism as they grew out of the military-industrial complex, and X-Men who more than ever represented a marginalized minority population. Ellis provided the final piece: A Fantastic Four as young scientists keen on exploration, activism, and huge society-altering ideas.

It’s a Marvel comic, so Ellis doesn’t quite get the chance to go deep, but in being limited to 18 short issues he inadvertently provides a perfect introduction to the concept (and the thrill!) of responsible scientific exploration. The little details are engrossing: After becoming stretchy, Reed Richards’ digestive system gets replaced with a “bacterial stack” that instantly digests everything. (I didn’t need to know where Reed’s food goes when he stretches, but answering it anyway brings a whole new dimension to the story, and encourages the reader to Rethink Everything.) Later on, when they explore the Negative Zone, the team renames their craft “Space Shuttle Awesome,” then spends an entire issue on the intricacies of first contact protocols. It’s an interesting way to prove that doing one’s homework can lead to fun fun fun. In a superhero book!—Chris

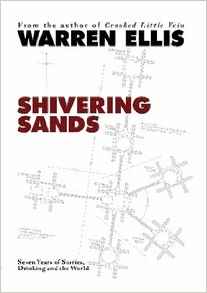

Shivering Sands

Ellis’s self-published collection of internet ephemera—essays share space with recipes; short, ferocious musings alternate with columns and other rambles—is like a time capsule of the early 2000s. Though it came out in 2009, it sat on my shelf until last year. As a result, reading it was a trip—a wry reminder of how much of the internet has changed, and how much of it really hasn’t. Still, Shivering Sands captures the way writing—and living—on the internet used to be: unfiltered, possibly tipsy, a little on edge, presenting a glorious hodgepodge of more than just the carefully cultivated pieces of a personality. It made me want to be a little freer, and it made me want to quit social media, all at the same time. —Molly

Ellis’s self-published collection of internet ephemera—essays share space with recipes; short, ferocious musings alternate with columns and other rambles—is like a time capsule of the early 2000s. Though it came out in 2009, it sat on my shelf until last year. As a result, reading it was a trip—a wry reminder of how much of the internet has changed, and how much of it really hasn’t. Still, Shivering Sands captures the way writing—and living—on the internet used to be: unfiltered, possibly tipsy, a little on edge, presenting a glorious hodgepodge of more than just the carefully cultivated pieces of a personality. It made me want to be a little freer, and it made me want to quit social media, all at the same time. —Molly

There are more, so many more, but it wouldn’t be fair to list everything. What Warren Ellis stories have stuck with you?